This article was written by Michelle Hayman and forms part of the SAHO Public History Internship

The ‘People’s Doctor’

‘He struggled to liberate society from oppression. He gave his life so that others may have a better life. He was a true patriot as a man of unity in the struggle against apartheid. His sacrifices were not in vain as his principles, beliefs and action touched many communities and helped to restore the dignity of destitute people’ (Prayer for Dr. Asvat, 2010).

Childhood and Schooling

On 23 February 1943, Abu Baker Asvat was born in Vrededorp(Fietas), South Africa.He spent his youth in Fietas, playing football and cricket on the playing grounds near his house. His father and grandfather worked in a nearby shop which his grandfather established after immigrating to the Transvaal from Gujarat. Though born to a family of merchants, Asvat’s father strongly encouraged Abu and his brothers, Ebrahim and Mohammad, to pursue medical careers.

In 1961, Asvat graduated from Johannesburg Indian High School and left South Africa to pursue a two year science course in Lahore, Pakistan. After completing his degree, he moved to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to begin his medical training. He and his brother Ebrahim eventually moved to Karachi where they completed their schooling. It was in Karachi that Asvat first became actively involved in anti-apartheid politics. Sometime around 1964, Asvat and his brother helped establish the Azania Youth Movement, a liberation organization affiliated with the Pan African Congress, in Karachi.

Coronation Hospital

When Asvat returned to South Africa after spending more than a decade abroad, he found a job as an intern at the Coronation Hospital in Johannesburg. He worked directly under Yosuf (Joe) Veriava who became a lifelong friend. However, Asvat was deeply uncomfortable with the blatant racism in the hospital towards both patients and staff. He eventually complained to the hospital administration after a pharmaceutical representative only talked to White doctors during a visit to the hospital. In response, the hospital fired him with less than 24 hours’ notice.

The ‘Chicken Farm’ Clinic

In 1972, shortly after his dismissal, Asvat took over a clinic in Soweto from his brother Ebrahim. Rather than pursuing a well-paying medical job in Lenasia or elsewhere in Johannesburg, Asvat felt his services were most needed in the township. The surgery was located in MacDonald’s Farm, known locally as the Chicken Farm area, where a shack community of around 60 families had developed. The surgery itself was located directly across from the Regina Mundi Church, a well-known meeting place in the anti-apartheid struggle. When Asvat arrived in the community, there were no working toilets or running water. Asvat quickly developed a close relationship with many of the families living in the community, providing individuals with blankets, food and small loans when necessary.

The clinic was small; it had one waiting room, a small examination room, and a toilet. Asvat would often see his patients free of charge, based on their own financial ability, sometimes seeing up to 100 patients a day. Asvat soon became well-known throughout Johannesburg for his dedication to helping people, as well as for his unassuming style. People from throughout Soweto came to him for medical services. He insisted that patients call him ‘Abu’ rather than Dr. Asvat. Ruwaida Halim, his former nurse, recalled that when Asvat was with patients, ‘he wouldn’t be a doctor. He would be a part of the people’ (Halim, 2010). His presence in the community quickly developed beyond his practice. He brought in portable toilets for the community to use and created a school out of a broken bus near his clinic.

His approachability and commitment to the community led patients to nickname Asvat ‘the People’s Doctor.’ In 1976, the community in Soweto demonstrated the respect they held for Asvat by protecting his clinic during the uprisings. After his clinic caught on fire during a showdown around his surgery, locals put out the flames and protected the surgery until Asvat was able to return the next day.

‘Hurley’

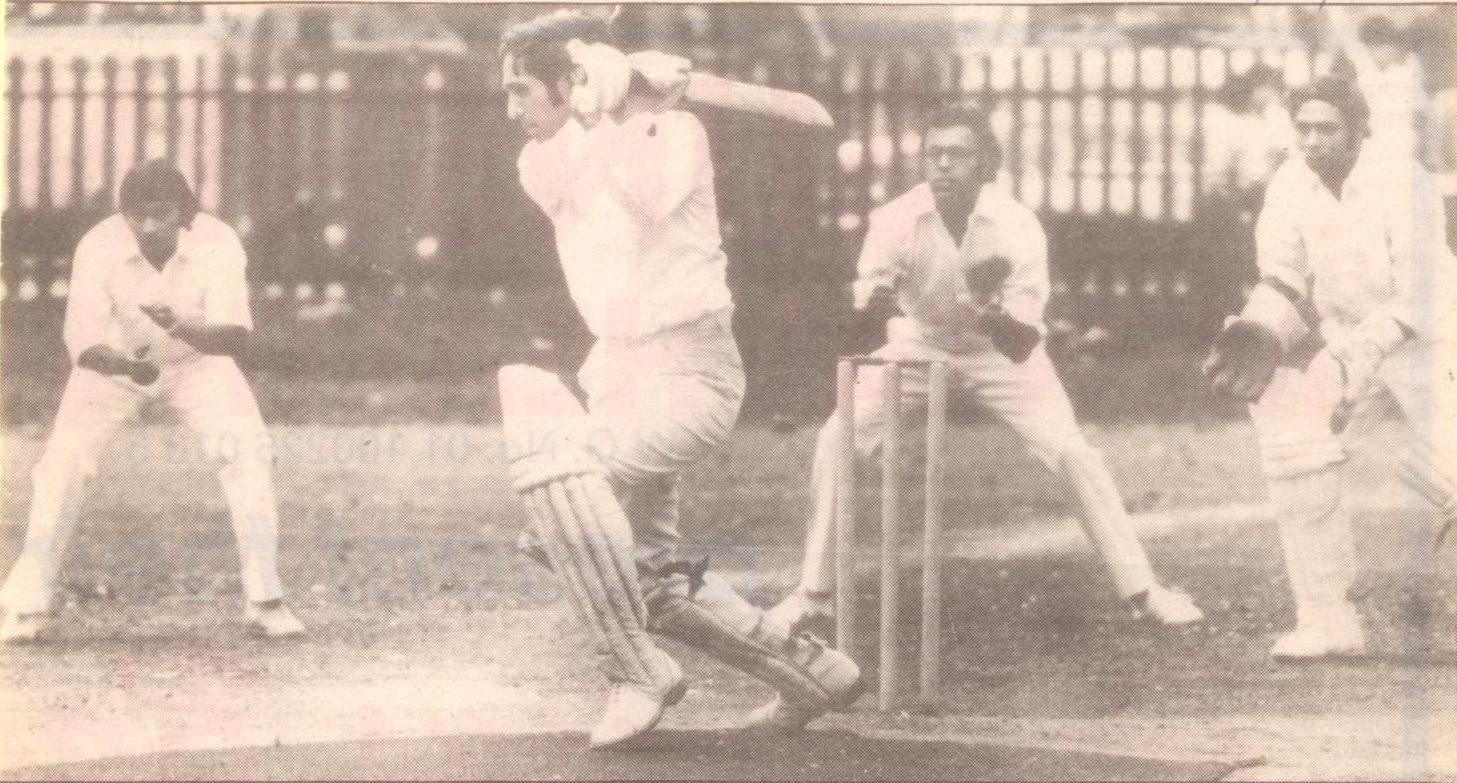

‘To white sportsmen, cricket is a game- but to us, it represents an area where we are privileged to have freedom of choice. In other words, for the sake of some 20 Sundays a year, we are regarded as equals on the cricket field.’ (Asvat, 1980)

Besides medicine, Asvat’s other great passion in life was cricket. His skills as a sportsman earned him the nickname ‘Hurley,’ which friends and family called him both on and off the field. For almost his entire adult life, Hurley played for the Crescents, a local team based in Lenasia. His passion for cricket extended past the playing grounds and into the political realm; in fact, to him they were never separate.

In 1976, the cricket community split over the politics of race when Ali Bacher and the South African Cricket Union introduced ‘Normal Cricket’ to playing fields across the country. ‘Normal Cricket’ was an attempt to integrate the sport in South Africa, allowing Black teams to play White teams on White playing grounds. Bacher incorporated this policy as an attempt to reintegrate South African cricket into the international leagues where it was excluded due to its racist policies. At first, Asvat and his fellow teammates were excited by the possibility that South African sport was progressing beyond racial policies. In a newspaper article published in 1983, Asvat recalled his initial optimism about the prospect of normal cricket.

‘Having been one of the many who ushered in the era of so-called normal cricket in 1976, I was filled with tremendous expectations that this was the dawn of a new era. It was exciting to think that, from then on changes away from apartheid would be rapid and that soon cricket would be given the honour of having led the country to this dream called freedom. But alas, it was not to be.’ (Asvat, 1983)

It did not take long for Asvat and many others to become disillusioned with the prospect of ‘non-racial’ cricket. They played in the league for a short time until an incident at a tournament in Northern Transvaal. Hurley and his teammates wanted to buy a celebratory round of drinks after winning the final game, but they quickly discovered that no stadium venue would serve them. This incident led Asvat and others to reject ‘Normal Cricket,’ and he refused to continue playing in the league. He came to the conclusion that competition between race-based teams in otherwise racially exclusive stadiums only encouraged the apartheid system of power.

‘No Normal Sport in an Abnormal Society’

Asvat was not alone in his disappointment with the non-racial cricket experiment. Led by Hassan Howa, the South African Council of Sport (Sacos) rejected ‘Normal Cricket’ under the slogan, ‘no normal sport in an abnormal society.’ Inspired by this move, Asvat began meeting with Ajit Gandabhai and Rasik Gopal, members of the Transvaal Council of Sport. Together they created the Transvaal Cricket Board (TCB) in 1977, a Sacos-associated rebel cricket league. The TCB claimed that normal cricket was multi-racial, rather than non-racial, as it still embodied apartheid race divisions. Asvat was elected honorary vice president of the new organization. This was particularly notable as the majority of the TCB membership was aligned with the Transvaal Indian Congress, while Asvat was a member of the Black Consciousnessmovement.

The Transvaal region became a focal point of debates over the feasibility of normal cricket. In 1979, Asvat was elected president of the TCB. He quickly became one of the most vocal spokespeople in South Africa against multiracial cricket. Speaking on behalf of the TCB in 1980, Asvat argued that,

‘Multiracial cricket can exist only in a racially orientated society whereas non-racialism cannot. The present exercise of those involved in ‘normal’ cricket is not an effort to transform society into a better one but merely to maintain white sporting privilege in the international context.’ (Asvat, 1980)

Spurred by his strong beliefs, Asvat entered into a public media debate with Ali Bacher over the best method to improve cricketing opportunities for Blacks. For Asvat, it was impossible to separate politics from sport, for as he stated, ‘sport is a microcosm of life’ (Asvat, 1980). Non-racial sport was impossible because the inequalities between races in cricket started long before the level of professional play. According to Asvat, state level racism manifested in cricket through less funding for schools, poorer equipment, and the nutritional issues associated with poverty. He published articles and wrote open letters to newspapers protesting the SACU-associated Transvaal Cricket Council’s attempts to recruit Black players into their league. When Alvin Kallicarran agreed to play for Transvaal province, Asvat published open letters of protest addressed to the well-known former West Indies cricket captain explaining the political ramifications of his actions.

In 1980, Asvat and the TCB organized a protest against the re-opening of a newly renovated stadium in Lenasia. SACU rebuilt the stadium to promote normal cricket in the township and the province as a whole. The TCB’s protest was extremely successful; according to newspaper reports, protestors constituted the majority of the spectators and were able to prevent the first match from occurring. Shortly after the protest, Indian and coloured students launched a nationwide school boycott. In Lenasia, protestors associated normal cricket with collaboration when they compared the expensive new stadium to their rundown high school. The Transvaal region was integral to the success or failure of normal cricket, and the TCB made it exceedingly difficult for the league to succeed. Eventually, in August 1982, Ali Bacher publically stated that normal cricket was dead.

In 1981, Asvat stepped down from the leadership of the TCB, based on the belief that no president should lead the organization for more than two years. Under his leadership the league had grown enormously. At its foundation in 1977, the league had less than a dozen teams; by the time of Asvat’s resignation, 42 teams were registered for the next season of play. The popularity of the league is particularly notable as the TCB was still banned from playing in many townships, including Lenasia. After his resignation, Asvat continued to play for the Crescents and remained an active cricketer for the rest of his life. In the late 1980s, he became involved in sports administration once more when he played a central role in creating a junior cricket league in Lenasia. Through incorporating sports and politics, Asvat was able to instill an awareness of political issues into a new generation of cricketers in the TCB. To the Crescents, Asvat was ‘our president, our guide, our comrade, our friend, our mentor, our backbone, our father, our brother’ (Crescents Cricket Club Statement, 1989).

Azapo

Asvat’s ideological commitment to Black Consciousness (BC) was central to his outright rejection of normal cricket. He first became involved in the Black Consciousness movement shortly after the police repression of the Soweto Uprising, around the same time as the ‘normal cricket’ debates. He felt that BC addressed issues he grappled with on a daily basis, including the divisions between African and Indian communities. Driven by the brutality of 1976, Asvat asked Joe Veriava how he might become involved in the movement. Joe connected Asvat to his brother Sadecque, who was then Vice-President of the Black People’s Convention for Education and Culture.

Asvat joined the Black Consciousness movement during a period of intense state repression. The arrest and death of Steve Biko in 1977 deprived the movement of its leader and led to the banning of all BC organizations in October of that year. However, the movement’s leaders quickly regrouped in 1978 to form the Azanian People’s Organization(Azapo). Now deeply committed to the movement, Asvat was a founding member of Azapo at its inaugural conference in April 1978. Later, Asvat was elected as Azapo’s Health Secretary.

Asvat was drawn to Black Consciousness for two primary reasons. Firstly, he felt that the identification of ‘Blackness’ as a state of mind rather than as a skin pigment could be used to overcome the divisions between the Black, Indian and Coloured populations. He himself identified as Black. As a doctor living in Lenasia, but working in Soweto, Asvat was acutely aware of the symbolic and material divisions that existed between the two communities despite their physical adjacency. He felt that Black Consciousness provided an ideological framework which could bridge the differences between these two communities.

Secondly, Black Consciousness’s commitment to community projects resonated with Asvat’s own approach to health care. Black Community Programmes were a key component of the early BC movement. In order to achieve the goal of infusing ‘the black community with a new-found pride in themselves (Biko 1971),’ BCP provided literacy and work training, published newspapers, and provided health care. Asvat approached his work through a similar mindset, believing that health care could help both the individual and the community. As he once told Sadecque Veriava, ‘The only way you can communicate with people is through work’ (Soske, 2011).

The Community Health Awareness Project (CHAP)

In 1982, the Transvaal region was facing a major health crisis when a cholera epidemic struck, followed by an outbreak of polio. In the context of these epidemics, the Azapo Health Secretariat launched the Community Health Awareness Project (CHAP) in July 1982. As Health Secretary, Asvat headed the project, which focused on preventative and primary health care. The project was designed to help overcome some of the inadequacies created by the apartheid system of health care and unequal living conditions. As Asvat once stated, ‘It goes without saying that the health services are inexplicably tied to the politics of this country’ (Asvat, ND).

Asvat’s understanding of well-being was greatly influenced by a worldwide discourse on health and development, in particular the Alma Ata declaration. The 1978 Alma Ata Conference provided an important model for health and well-being in developing countries which resonated with the language of Black Consciousness. The declaration described health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,’ and contended that health was essential to economic development. The health projects initiated by CHAP and Azapo demonstrated this same commitment to complete well-being.

Handbook on Health

In March 1984, the Azapo Health Secretariat released a twenty page handbook on health, which gave clear and simple medical advice on preventive and primary health care. Asvat wrote the pamphlet, which provided information on children’s health, breast feeding, cholera prevention, first aid, and preventing the spread of venereal diseases. A significant section of the work was devoted to discussing the rights of patients. The manual was published in English, sePedi, isiZulu and seSotho. It officially cost 50 cents a copy, although Azapo would provide the manual for free upon request. Through Azapo’s existing health networks, the handbook reached large numbers of South Africans. On one occasion, the Health Secretariat distributed up to 5,000 copies in one day. In the manual, Asvat stressed the political dimensions of health, stating that,

‘While the minority white privileged class enjoy health facilities which are on the same level with most of the first world countries, the vast majority of Blacks, who also happen to be unenfranchised, underprivileged and forgotten people, in some cases enjoy no health facilities at all.’ (Asvat, 1984)

Mobile Clinics

One of CHAP’s most well-known programmes was a mobile health clinic which travelled across the country throughout the 1980s. Asvat and a team of volunteers travelled throughout South Africa, aiming to provide primary health care to some of the nation’s most disadvantaged areas. The team included a core group of volunteers, nurses, dentists, optometrists and social workers, including Azapo comrades Thandi Myeza, Jenny Tissong and Ruwaida Halim. These clinics would provide blood pressure testing, urine samples, and other forms of preventive testing. On most weekends, Asvat and his team would travel with the clinic, and he continued to work at his Soweto surgery during the week. During outbreaks of violence or epidemics, Asvat’s team would often arrive on the scene to provide medical care for victims. For instance, in February 1986, Asvat set up a clinic in Alexandra to help those hurt during the violent uprising.

These mobile clinics received considerable attention from the South African press, particularly during their visits to the area of Brantford. In 1977, Winnie Mandela was banished to Brantford and during her banning she built a community clinic in the area with help from Asvat. The two first met through Joe Veriava who was working as Winnie’s primary care physician. After travelling with Veriava to Brantford on several occasions, Asvat eventually took over as her doctor. Since her banning, Winnie had been working to provide community services to Brantford through the organization Operation Hunger. When the CHAP clinic came to Brantford, Operation Hunger provided food and transportation for patients.

The CHAP clinics contained a strong focus on women’s health. For instance, in April 1985, Azapo teamed up with the Ikageng Women’s Group to create a free monthly health clinic which provided preventive health services for women and children, including testing for cervical cancer, diabetes and malnutrition. After the minister of health declared the government would not provide free pap smears to women, Asvat and a team of dedicated nurses and volunteers began a cross-country clinic that would provide this service to Black South African women.

By travelling to remote rural areas, Asvat’s team was also able to provide isolated and doctorless communities with the knowledge to protect their own physical well-being. At these clinics, volunteers would distribute the Azapo Health Manual, as well as manuals developed on other topics such as preventing the spread of AIDS (written in 1988). In addition to clinics, Asvat would address church congregations and other community groups about basic preventive health care.

As shown through CHAP’s work with the Ikageng Women’s Group, the mobile clinics were often a partnership with individuals and organizations already working in the area. They allowed CHAP to connect with the community through the pre-existing informal health care networks. By working with local nurses, social workers and medical students, the mobile clinic was also able to help improve the limited on-the ground services available, through training and supplies. For instance, after CHAP ran a mobile clinic in Winterveldt, a group of medical students were inspired to start their own free clinics in the area. In the absence of any medical infrastructure, these mobile clinics provided basic medical services and helped the development of long term systems for community health.

Family Life

It was extremely important to Asvat that his family play a role in his medical and political projects. He met and married his wife Zorah during 1976, when his clinic was becoming well-known throughout the area and he was becoming increasingly involved in Black Consciousness. They lived in Vredersdorp for a short period after their wedding, but were forced out of the area due to conflict over the Group Areas Act. Afterwards, they moved to their home in Lenasia which Asvat’s grandfather had recently built. They remained in Lenasia, where they had three children together; Suleiman, Akiel and Hasina. His family was of utmost importance to Asvat. Even during the busiest periods of the CHAP project, he remained an active participant in family life, doing the grocery shopping and readying their children for bed.

Zorah would occasionally come to work with Asvat, helping run the soup kitchen and crèche near his clinic. Their three children also sometimes accompanied their father during his weekend clinics in the townships and around the country. Though Zorah protested Asvat’s decision to take their children into more dangerous areas during his work, he firmly believed that their children ‘must see poverty’ (Zorah, 2010). Faith also played an extremely important role in both Asvat’s work and his family life. At the end of every day they recited prayers together as a family. Each year, the Asvat family would share their Eid meat with their friends in the community around the surgery.

Albertina Sisulu

In 1984, Asvat found a new partner in his quest to provide medical services to the African community. Albertina Sisulu, the famed UDF leader and wife of imprisoned ANC hero Walter Sisulu, had just been released from prison when Asvat offered her a job working as a nurse in his Soweto clinic. The clinic was in the area Albertina was limited to work within due to her police banning. The two quickly developed a close partnership; Elinor Sisulu described them as ‘kindred spirits’ who were both committed to overcoming the plight of homelessness and overthrowing the apartheid state (Sisulu, 2003). Understanding her situation as a political leader, Asvat allowed Sisulu the flexibility to continue her work with the UDF and visit Walter on Robben Island. Asvat also continued to give Albertina wages during periods when she was contained by the police. Albertina Sisulu later described their relationship as one between ‘a mother and a son’ (Russel, 1997).

In the context of the mid-1980s, their partnership was remarkable. In 1984, the tenuous relationship between the UDF and Azapo broke down into warfare between cadres from the organizations. Over the next few years, hundreds (though some estimates are in the thousands) of Azapo and UDF youth were killed in political violence in the townships. Yet Asvat and Sisulu’s political allegiances never interfered in their friendship or work. Sisulu’s role in the UDF did not prevent Asvat from using the clinic as a meeting place for Azapo comrades and the two provided emergency treatment for injured fighters regardless of political association. Together, the Azapo Health Secretary and UDF co-president were a symbol of unification in an area torn apart by deadly internal violence. In 1988, their importance as community leaders was reflected when Black students graduating from Wits Medical School requested that both Asvat and Sisulu sign and confer their medical degrees for an alternative Black graduation ceremony.

The Anti-Asbestos Campaign

Shortly after Asvat hired Albertina, Azapo started a new health project in conjunction with the Black Allied Mining and Construction Workers’ Union (BAMCU). In October 1984, BAMCU and Azapo launched an Anti-Asbestos Campaign after labour unrest following layoffs of 1700 union members from an asbestos mine in Penge, one of the largest mining projects in Northern Transvaal. At the time, South Africa was the only producer of brown asbestos in the world and one of the largest producers of blue asbestos (crocidolite). The campaign focused on promoting awareness of the health dangers of the material with the long term goal of shutting down asbestos production in South Africa. BAMCU and Azapo encouraged workers to refuse to work in the mines and for communities to boycott asbestos products. BAMCU was well aware their campaign would result in job loss for the black community, but they argued that the health risks associated with asbestosis were not worth the minimal wages paid to black miners. As they stated in their campaign announcement, ‘We’d rather starve than sell our lives’ (van Niekerk 1984).

As Health Secretary of Azapo, Asvat played a leading role in the campaign. He publically called for the government to provide equal compensation for miners affected by asbestos-related illnesses, no matter their race. He published articles explaining the dangerous health impacts of mining asbestos, including asbestosis (pulmonary fibrosis), lung cancer and mesothelioma. He used his considerable influence in the Lenasia community to urge citizens to reduce their use of asbestos products (Asvat 1984). Calling for the eventual closure of the asbestos mines, Asvat argued that ‘although we may be classified a Third World country, our citizens deserve First World treatment’ (Molefe, 1984).

The People’s Education Committee

In 1986, Asvat once again demonstrated his ability to work with individuals from across political boundaries through his involvement in the education crisis. Throughout the 1980s, school boycotts destabilized the townships, as thousands of students moved out of the classrooms and on to the streets with the call for ‘Liberation Now, Education Later.’ As the Sowetan journalist Nomavenda Mathiane wrote in 1986, ‘As things stand in Soweto and most townships, schooling has long ceased to be an educational matter. It is political’ (Mathiane 1986, 1989). The boycotts descended into violence on the part of both the students and the state.

In late 1985, the National Education Crisis Committee (NECC) formed to attempt to address the quickly deteriorating situation. Before their inaugural conference in March 1986, the People’s Education Committee (PEC) was formed in Lenasia to discuss NECC’s proposals for students, including the recommendation that they return to school. Though most PEC members were affiliated with the UDF, they elected Asvat as the first president of the organization. His friend Basheer Lorgat, a co-member of the PEC, later reflected on the significance of the committee’s decision to elect Asvat.

For Hurley to have been chosen to head up the People's Education Committee was in itself a very strong suggestion that he was the most able bodied person to implement the task at hand. Not only was the People's Education Committee involved in matters of education affecting the residents of Lenasia, but because of Hurley's tremendous profile amongst homeless people in communities surrounding the settled residents of Lenasia, Hurley was the ideal choice. (Lorgat, 2010)

As Lorgat’s statement indicates, the PEC was also involved in the issues surrounding the increasing number of Black homeless people in Lenasia. In and around the Indian township, there was a growing Black homeless community without access to education or health care because they were outside the boundaries of the Group Areas Act. One of the PEC’s greatest achievements was beginning to integrate these students into Lenasia schools. Asvat was critical to this process, using his reputation, political stature and connections to pressure school boards into accepting Black students from squatter communities. This process of integration contributed to the nationwide campaign to break down the barriers of apartheid education.

Fight for the Homeless

‘For the first time squatters could speak of a doctor, could speak of a person who would actually heal them, care for them, give them shelter.’(Asvat Memorial Service, 1989)

As his work with the PEC indicates, Asvat was particularly concerned about the well-being of homeless people in South Africa. He constantly aimed to help the homeless, whether through providing families with blankets and tents to sleep in or by protesting against planned removals. For instance in January 1986, Asvat launched a campaign to protest the eviction of 200 ‘squatters’ from their homes at Vlakfontein Farm. Assisted by the Witwatersrand Council of Churches and the Black Lawyers Association, the campaign was successful in convincing the West Rand Development Board to suspend the evictions indefinitely. He spoke out publically about the issue of homelessness in South Africa and called upon the government to address the growing number of squatter communities. As he stated in 1987, ‘All people all over the world have certain rights and the right to a home is one that no government can deny. Until such time that each and every one of us is adequately housed, we should not rest’ (Asvat, 1987).

Asvat also assisted the homeless by providing basic primary health services to squatter communities. His mobile clinics often visited ‘illegal’ settlements, such as the communities in Mathopestad and Protea. These efforts brought him into direct conflict with the West Rand Administration Board and the associated Soweto Council. In July 1983, the West Rand Administration Board (WRAB) confronted Asvat while he was assisting homeless people in Pimville Township replace their identity documents. The manager of the township ordered his arrest and expulsion from the area when Asvat refused to show his permit. In response, the WRAB declared him persona non grata.

Two years later, Asvat engaged in a public battle with the Mayor of Soweto, Edward Kunene, over housing eight families whose homes had been demolished by authorities. In a highly publicized incident, Asvat delivered the displaced families to the Mayor’s doorstep where Kunene promised to provide them with shelter. Later, when Kunene failed to uphold his commitment, Asvat housed the families on his own property, in defiance of the Group Areas Act.

Eviction

Eventually, Asvat’s fight against squatter camp clearances led to his own eviction. In January 1988, the Soweto Town Council announced they were bulldozing the MacDonald Farm to allow for a real estate development. Asvat received an ultimatum to leave his clinic within a week to allow for a clearance of the slum settlement. Initially, Asvat and Sisulu ignored these warnings and continued to provide medical care for the community even after their clinic was the only building left standing and the electricity had been cut off. Ultimately, they were forced to move and Asvat relocated the surgery to a house in Rockville, across from the Mchina squatter camp. By the time of Asvat’s eviction, the surgery had become famous throughout South Africa for its role in the struggle.

The Murder of Abu Baker Asvat

At the time Asvat moved his surgery to Rockville, he was aware that his life was in serious danger. In 1986, arsonists attempted to burn down his family home; the following year two men armed with knives attacked Asvat in his surgery, but he fought them off. In 1988, a man pulled a gun on Asvat in his surgery, but fled when a patient entered the room. In response to these increasing threats on his life, Asvat installed an automatically locking door between the waiting area and the examination room of his new surgery. According to his family and friends, Asvat, a man who always insisted that Soweto was safe, appeared unusually nervous in the weeks before his death.

On 27 January 1989, Asvat’s life came to an end at age 45 when two armed men posing as patients shot him in his Rockville clinic. Albertina Sisulu later testified that the two men arrived early in the afternoon and registered with Sisulu for an appointment. The men then disappeared for a short period of time, returning around 4pm. Shortly thereafter, Sisulu heard two shots fired in the examination room. She ran outside to call for help and when she returned she found that Asvat was fatally wounded. She sat next to him as he died, waiting for an ambulance to arrive. Later, she later told Asvat’s relatives that ‘My son died in my hands’ (Asvat Memorial Service, 1989).

Asvat’s Funeral

In accordance with Islamic tradition, Asvat’s funeral took place the next day. According to the newspaper The Sowetan, it was the largest funeral ever to occur in Lenasia, with approximately 6000 mourners in attendance (other sources claim there were up to 10 000 present). People drove from across the country for his funeral. Those in attendance remarked on the incredible diversity of the mourners. Indians and Africans, Azapo and UDF, ‘squatters’ and political leaders all arrived to pay their respects to ‘a son of the soil.’ After the service, mourners sang struggle songs and waved the Azapo flag as they accompanied Asvat’s coffin to his burial site in Avalon Cemetery. Though police attempted to confiscate the Azapo banners and arrest activists in the crowd, the mourners were able to scare them off without resorting to violence.

Over the next few days, there were memorial services in Lenasia and Soweto, allowing those who were unable to arrive in time for the funeral to honour Asvat’s life. As Joe Veriava, Asvat’s former boss and comrade stated at the memorial service in Lenasia, ‘We have not come here to mourn his death, but to pay a tribute to a son of Africa’ (Veriava, 1989). Individuals from across political parties and walks of life attended these tributes. In the week following Asvat’s death, newspapers across the country published articles and obituaries honouring the fallen doctor’s life. The Lenasia Indicator dedicated an entire issue in commemoration of Asvat and his work. Those papers who presented Asvat as a solitary philanthropist received letters from his comrades who reminded readers that ‘Asvat was more a revolutionary than a mere humanitarian.’ (July, 1989).

Who killed Dr. Asvat?

At the same time newspapers were commemorating Asvat’s life, the media was also debating the cause of his murder. Shortly after his death, police declared that the killers’ primary motivation had been robbery, claiming that R135 was missing from the examination room. A few weeks later, police arrested two young men, Zakhele Mbatha and Thulani Dlamini, on the charges of theft and murder. Later, Asvat’s family reported to the media that they found no money or valuables missing from the clinic.

Less than a week after Asvat’s death, newspapers began to report that Winnie Mandela believed that there was a political motivation behind his murder, connected to the Mandela United Football Club’s (MUFC) abduction of four young boys from a Methodist manse the previous December. According to these reports, Mandela claimed that Asvat would have been a potential professional witness to her claims that the boys were being sexually abused at the church.

Shortly thereafter, media sources began to report that, conversely, Asvat’s death was related to his potential role as a witness against Mandela in the kidnapping controversy. Sources claimed that the previous December, Asvat had examined Stompie Seipei, the kidnapped boy who was later found dead, and urged Winnie to send him to a hospital. These reports claimed that Mandela thus had a motivation to silence Asvat.

Despite these claims, the police investigation continued under the belief that robbery was the primary motivation for murder. In November 1989, Zakhele Mbatha and Thulani Dlamini were found guilty and sentenced to death in a highly publicized murder trial. Asvat’s brother Ebrahim spoke publically against the trial verdict, stating his brother would not have supported the death sentence. In 1991, after reforms in the South African legal system, Mbatha and Dlamini protested their original sentence and were awarded a new trial. The court once again found both men guilty on the charges of assault and robbery, but changed their sentences to lifetime imprisonment.

Over the next few years, various claims regarding the relationship between Asvat’s death and Stompie Seipei’s murder (which Winnie Mandela was convicted in connection to in 1991) occasionally surfaced in the South African media. In 1997, these claims received an official investigation by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as part of the special inquiry into Winnie Mandela and the Mandela United Football Club. Once more, Asvat’s family asked for anyone with information about his death to come forward and testify at the trial. Ultimately, however, the TRC was unable to establish if Winnie Mandela played any role in Asvat’s death. Winnie Mandela has always maintained she was not connected in any way to his murder. Whether or not she played a role in the death of her former doctor and friend remains a contentious issue to this day.

The Abu Asvat Institute for Nation Building

At the same time these debates were occurring, a dedicated group of Asvat’s comrades and friends were working to preserve the memory of Asvat’s life in the wake of the controversy of his murder. A year after his death, the first Dr. Abu-Baker Asvat Memorial Cricket tournament was held in his memory in Lenasia. The tournament continues to run as an annual event to this day, organized by the Abu Asvat Institute for Nation Building. In February 2012, the Institute, in partnership with Azapo, hosted the inaugural Abu Asvat Memorial Lecture, given by Mosibudi Mangena. In the speech, Mangena, the president of Azapo, reminded listeners that Asvat was “a man who unreservedly committed himself to the struggle of his people for freedom; who steadfastly defied the oppressor; who devoted all his energies, talents and professional skills to the service of the poor” (Mangena, 2012). Asvat’s incredible legacy as a doctor, cricket player and comrade continues to live on.

Asvat, Dr. Abu Baker, 1984, ‘Asbestos Danger!’ Lenasia Times, November.|Asvat, Dr. Abu Baker 1980, ‘Title Unknown,’ Rand Daily Mail, 28 August.|Asvat, Dr. Abu Baker 1983, ‘Money is Temporary, Honour is Permanent,’ Rand Daily Mail, 26 January.|Asvat, Dr. Abu Baker 1987, ‘Tend to the Basic Needs of the Homeless First,’ 20 September.|‘Azapo Helps with Health,’ Lenasia Times, March 1984.|Biko, Steve 1978, I write what I like, London: Bowerdean Press.|‘Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care,’ Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf.|July, Jerome 1989, ‘Letter to the Editor,’ Weekly Mail, 24 February.|Marx, Anthony 1992, Lessons of Struggle, Oxford: Oxford University Press.|Molefe, ZB 1984, ‘It’s do- or die!” 14 October.|Russel, Cecilia 1997, ‘Shock waves from Albertina’s Testimony,’ The Star, 2 December.|Sisulu, Elinor 2003, Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime, London: Abacus.|Soske, Jon 2011, ‘The Life and Death of Dr Abu Baker ‘Hurley’ Asvat, 23 February 1943 to 27 January 1989,’ African Studies, v70 n3: 337-358.|The Crescents Cricket Club 1989, ‘Team Statement,’ The Indicator (Asvat Memorial Edition), 8-15 February.|‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume Two’, South Africa, 29 October 1998. http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/finalreport/Volume%202.pdf|Van Niekerk, Phillip 1984, ‘Union calls for Boycott of Asbestos Products,’ Rand Daily Mail, 12 October.