The HIV/AIDS Crisis Emerges: Reponses of the Apartheid Government

In 1982, the first case of AIDS in South Africa was reported in a homosexual man who contracted the virus while in California, United States. Later that year, 250 random blood samples were taken from homosexual men living in Johannesburg, of which a startling 12.8% were infected with the virus.

The first deaths from AIDS in South Africa occurred in 1985. The apartheid government of President P.W. Botha subsequently held a conference to address the potential threat the disease posed for the country. In 1987, regulations were issued that added AIDS to the official South African list of communicable diseases. These regulations called for a mandatory 14-day quarantine for individuals suffering, or suspected of suffering from AIDS. The quarantine could be extended indefinitely if a case was confirmed. Later that year, the first black South African was diagnosed with AIDS.

In 1988, a structure called the AIDS Unit and National Advisory Group was erected within the Department of Health to promote awareness about HIV/AIDS. It consisted of a small group of officials who were made responsible for addressing the emerging pandemic.

The scope of these early efforts by the apartheid administration remained minimal, however, and by 1990 an estimated 74,000-120,000 South Africans were living with HIV. That year, a national antenatal survey was conducted for the first time, and found 0.8% of pregnant women to be infected. In April, the issue was raised at the Fourth International Conference on Health in South Africa. A document was released following the conference to address the most pertinent elements of combatting the disease, including prevention and human rights protections for the infected. This document was entitled ‘The Maputo Statement on HIV/AIDS.’

In early 1991, a national conference was held and a new body called the National Advisory Group (NACOSA) was established to develop more comprehensive government policies for HIV/AIDS. NACOSA was meant to bring actors from a range of sectors together to develop a cohesive response to the crisis. The government’s AIDS Unit was dismantled later that spring, and replaced with the National AIDS Programme.

By July, the number of AIDS cases contracted through heterosexual sex was equal to those contracted through homosexual sex, a statistic that challenged widespread prejudice that HIV/AIDS was a ‘gay disease.’ From that point on, heterosexual sex became the dominant mode of HIV transmission in South Africa. However, a great deal of stigma continued to surround the disease and in the early 1990s some prominent white leaders publically claimed that a supposed ‘promiscuity’ of gays and blacks was the reason for higher than average contraction levels of these two populations. In 1992 a member of the apartheid parliament took such racist claims even further by promoting the utilisation of the disease as a tool to rid South Africa of its black population. This threat was made very potent by the fact that in the final years of its existence, the apartheid government had sponsored the development of biological weapons and forced sterilisation to potentially use against black South Africans.

A New Democratic Era: Responses of President Nelson Mandela’s Administration

On 10 May 1994, the Government of National Unity was elected in South Africa’s first democratic elections. Nelson Mandela became president, and Dr. Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma was appointed as Minister of Health. One month later, combatting HIV/AIDS was made one of 22 lead projects of the new government’s Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). Three new structures were proposed in the RDP that focused on encouraging engagement with civil society in writing government HIV/AIDS policy: (1) an HIV/AIDS and STD Advisory Group; (2) a Committee on NGO Funding; (3) a Committee of HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Research.

AIDS organizations and activists celebrated the professed commitment of the new government to tackling the disease. In August, President Mandela’s government accepted ‘The National AIDS Plan for South Africa’ launched by NACOSA. The plan focused on prevention of HIV through public education campaigns, reducing transmission of HIV through appropriate care, treatment and support for the infected, and mobilizing local, provincial, national and international resources to combat HIV/AIDS.

The following year, from 6-10 March the 7th annual International Conference for People Living with HIV and AIDS was held in Cape Town. Over 476 people attended from a total of 84 countries. This was hailed as an important moment in promoting South Africa’s involvement with the international community in combatting the pandemic.

By August, however, optimism began to turn into disillusionment. The Department of Health spent R14.27 million that had been provided by the European Union for combatting HIV/AIDS in South Africa on a play called Sarafina II. This project was designed to educate the public, particularly youth, about the disease. However, critics and HIV/AIDS activists alike denounced the play’s script as inappropriate and unclear, and prominent AIDS organizations expressed deep discontentment over being excluded from the planning and execution of the project. Consequently, government funding for the play was halted in 1996, and its ultimate failure confirmed a growing consensus among civil society actors that the response of the newly democratic South African government to the worsening pandemic was turning out to be grossly insufficient. Indeed, Nelson Mandela himself later called the poorly conceived and mismanaged Sarafina II one of the major mistakes of his administration.

In 1996, Rose Smart was appointed as director of HIV/AIDS and STD programming. However, this position was placed under the administration of the Health Department, rather than being given a more powerful seat in the President’s Office. This violated the terms put forth by the National AIDS Plan and suggested that the government continued to view the pandemic as solely a problem of public health, rather than a major social crisis that required broader government involvement.

On 22 January 1997 another high-level government scandal surfaced when Mandela’s cabinet received a presentation from researchers of the South African AIDS drug Virodene. Trials of the drug had been banned in South Africa by the Medicines Control Council (MCC) due to significant evidence that its main active ingredient- an industrial solvent- was extremely toxic. However, Health Minister Dlamini-Zuma supported public trials of the drug despite these concerns over its safety. He subsequently engaged in a number of unsuccessful attempts to publicly pressure the MCC to change its policy on the matter.

Later that year, the Department of Health reviewed the NACOSA Plan and found that there was a concerning lack of political leadership in combatting HIV/AIDS. A new plan called ‘The National AIDS Control Programme’ was thereby created by the Department of Health. Its goals were to reduce HIV/STD transmission by providing appropriate care, treatment and support for infected persons. By calling for a mobilization and unification of local, provincial, national and international resources, this plan emphasized the objectives of behavioral change, human rights protection of infected persons, mass media education and community support.

Then, in late autumn, a first ever high-level government body was formed to generate a cohesive response to the epidemic from a multitude of different departments. It was called the ‘Inter-Ministerial Committee (IMC) on AIDS,’ and Deputy president Thabo Mbeki was appointed as its chair.

At the beginning of 1998, a battle for the provision of anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) by the South African government that would last for much of the following decade began. South African AIDS activists and researchers alike called upon the government to distribute an ARV drug called Zidovudine (AZT) to pregnant women. However, all ANC-led provinces rejected the use of AZT, based primarily on claims that it was too expensive to distribute. Moreover, Health Minister Dlamini-Zuma openly opposed the drug, and asserted that the South African government’s policy was to focus on prevention rather than treatment. This argument seemed illogical to the Health Minister’s critics, however, as the drug has been shown to dramatically reduce HIV transmission from pregnant women to their unborn children.

At the end of the year, on 10 December, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) was launched by HIV-positive activist Zachie Achmat and ten other individuals. This organization aimed to protest the government’s refusal to distribute ARVs. The group’s members wore trademark t-shirts with ‘HIV-POSITIVE’ written in large letters, and Achmat made a famous pledge to not use ARVs until they became available to all South Africans.

The ambitious HIV/AIDS program outlined at the start of the Mandela presidency had by the end of 1998 fallen extremely short of expectations. Explanations for its ultimate failure have included that HIV/AIDS was heavily politicized along racial lines in the 1980s and early 1990s. It has thus been suggested that since Mandela worked throughout his tenure on promoting national reconciliation and inter-racial unity in South Africa, the crisis was de-emphasized by his administration as a means of diffusing racial tensions.

From Disorganisation and Mismanagement to Outright Denialism: Responses of President Thabo Mbeki’s Administration

On 14 June 1999, President Thabo Mbeki was elected as the second post-apartheid President of South Africa. Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang was selected as Minister of Health in his cabinet. Upon taking office, President Mbeki called upon all sectors of society to become involved in combatting the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

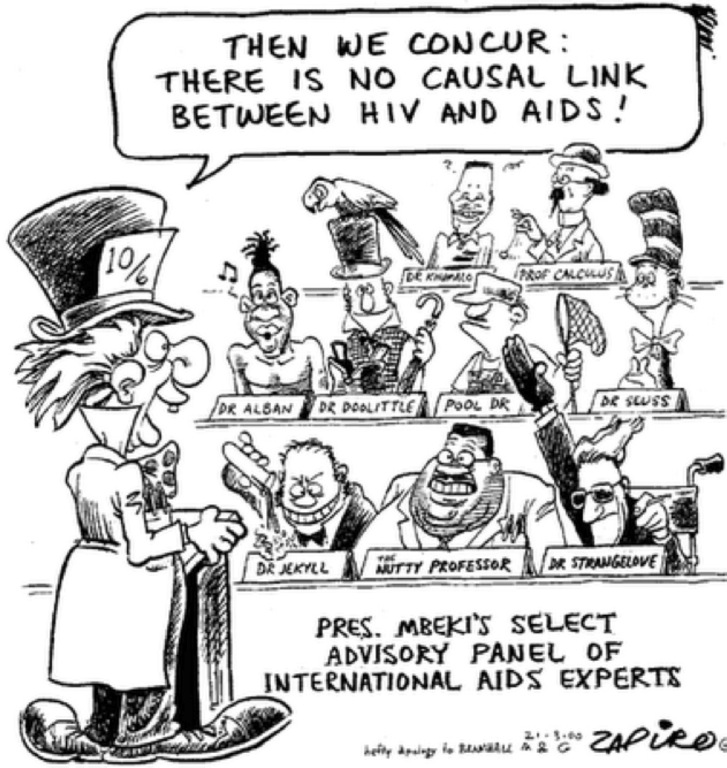

However, the President openly held the position HIV did not cause AIDS, and faced minimal dissent in his cabinet for his many public statements on the matter. In fact, at the beginning of 2000 Mbeki sent a letter to world leaders urging them to reconsider socioeconomic factors as the true cause of AIDS. He put together a panel of scientists who agreed with his position, although the rest of the international scientific community considered such views to be highly dissident.

Indeed, official South African HIV/AIDS policy had clearly stated that HIV caused AIDS for over a decade. Nonetheless, even Health Minister Tshabalala-Msimang refused to contradict the claims of the President. Explanations from scholars for this unquestioning acceptance of Mbeki’s Presidential authority have included that the ANC’s structure tends to promote an intolerance of voices dissenting from the center due to the hierarchy and discipline that were established within the party while its members were in exile. This, it has been argued, made it difficult for any ANC members to speak out against Mbeki’s unusual views without being called unpatriotic or counter-revolutionary. Moreover, Mbeki instituted a new system in which policy planning was made by ANC clusters across the country that he coordinated himself. This effectively created a more unilateral communication flow from the President’s office to the rest of the ANC party than had existed under Mandela.

In January 2000, The National AIDS Council (SANAC) was formed, replacing the Inter-Ministerial Committee on AIDS. The establishment of this council was coordinated by Health Minister Tshabalala-Msimang. It aimed to consolidate political leadership and increase civil society involvement in the fight against HIV/AIDS. In February, two major programmes were launched under the auspices of the council. First, the National Integrated Plan (NIP) for children infected and affected by HIV and AIDS was a joint venture of the departments of health, education and social development. It promoted three interventions: life skills education for youth, home/community-based care, and support for HIV-positive children through NIP funds. Second, the HIV/AIDS/STD National Strategic Plan for South Africa 2000-2005 promoted the two primary goals of reducing new infections (particularly among youths), and reducing the impact of HIV/AIDS on individuals, families and communities. Comprehensive plans for a mass-scale provision of ARV drugs remained notably absent from both of these major programmes.

On 19 April 2001, the South African government successfully protected a law to allow the domestic production of cheaper, generic brand medicines -including ARVs - against a lawsuit filed by transnational pharmaceutical companies. However, government provision of ARVs through public health structures after this victory remained remarkably low. Consequently, a year later the South Africa High Court ordered the government to make the antenatal drug Nepravine available to HIV-positive pregnant women. The South African cabinet also officially confirmed the policy that ‘HIV causes AIDS’ to cease any further speculation of this fact by government officials. Outright statements dissenting from this policy from both President Mbeki and Health Minister Tshabalala-Msimang were effectively halted.

Despite the order by the High Court, no mass-scale provision of Nepravine was executed. The Treatment Action Campaign consequently organized a movement at the start of 2003 to object to the South African government’s general failure to execute a proper response to the pandemic. In February, the organization coordinated a march of thousands of people on parliament to protest a lack of universally accessible ARVs through the public health system. One month later, a civil disobedience campaign was launched to heighten pressure on the Ministry of Health to issue a comprehensive ARV treatment plan.

Patients in Langa Township, Capetown receiving ARVs, January 2004. Photographer: Eric Miller. ©: Africa Media Online.

Patients in Langa Township, Capetown receiving ARVs, January 2004. Photographer: Eric Miller. ©: Africa Media Online.

Partly due to this increased pressure from civil society, the South African cabinet approved a plan for universal ARV treatment in August 2003. The programme began in March 2004 in Guateng, and expanded to other provinces soon thereafter. By March 2005, the target of the 2003 plan was met to have at least one service point for AIDS related care and treatment in each of the country’s 53 districts. However, the number of people actually receiving ARV treatment remained far below the objectives outlined in the plan. The government responded to this problem in the late fall of 2005 with a new policy framework in which a commitment to improving public access to ARVs was declared.

By late 2005, more than 5 million South Africans were HIV-positive, making South Africa the country with the highest HIV rates in the world. While the majority of the government continued with its new ARV-focused policy framework, Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang simultaneously promoted an alternative treatment campaign based on nutrition and palliative care. Scholars have called this program ‘nationalist’, or ‘ameliorative’ in contrast with more internationally accepted and scientifically proven biomedical responses to HIV/AIDS. The Health Minister advocated the consumption of African foods such as garlic, lemon and beetroot by HIV-positive individuals as a viable alternative to ARV treatment in preventing the onset of AIDS. In addition, she continued to make public statements insinuating that ARVs were toxic, with little scientific evidence to back her claims. The Health Minister’s promotion of alternative, ‘African’ remedies, and her criticism of an internationally sanctioned ARV response generated heated controversy from South African and international AIDS activists alike.

In May 2006, the Health Department initiated the development of a new 5-year National Strategic Plan (NSP) by SANAC, under the leadership of Deputy President Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka. The plan was launched on 12 March 2007, and called for a multi-sectoral response that expanded upon the NSP of 2000-2005. It focused on four key priority areas: (1) Prevention; (2) Treatment, care and support; (3) Human and legal rights; and (4) Monitoring, research and surveillance. While it was designed to flow from the NSP for 2000-2005, this plan contained a relatively heavier emphasis on ARV provision. Universal access to ARV treatment, however, remained far from realised.

On 25 September 2008, President Mbeki resigned from office due to having lost the support of the ANC. Kgalema Motlanthe was selected as interim president, and Tshabalala-Msimang was replaced by Barbara Hogan as Minister of Health.

Turning Poor Policy Around: Responses of President Jacob Zuma’s Government

On 22 April 2009, Jacob Zuma was elected President of South Africa, and Dr. Aaron Mostoaldi was appointed as Health Minister. AIDS activists initially responded to the election of Zuma with deep skepticism and wariness, as he was charged with the rape of an HIV-positive woman in December 2005. He was found not guilty on 8 May 2006, but made a number of controversial public statements about HIV/AIDS during the trial. For instance, in court he claimed that after intercourse with the woman he had taken a shower because “It”¦ would minimise the risk of contracting the disease.” (retrieved from: http://www.southafrica.to).

However, it soon became clear that the dissenting scientific views and denialism that defined Mbeki’s Presidency would not continue to prevail under the new government. By the late autumn of 2009, President Zuma’s cabinet publicised a commitment to test all children exposed to HIV and provide all HIV-positive children with ARVs. Moreover, as per the target set by the National Strategic Plan of 2007-2011, coverage of HIV-positive mothers with AZT treatment was estimated at over 95 percent by 2010. Transmission from mothers to their children was thereby reduced to just 3.5 percent.

In April, an HIV Counselling and Testing (HCT) media campaign was launched by the government to increase discussion of HIV in South Africa. It operated through door-to-door campaigning and billboards to promote the availability of free testing and counseling in health clinics, as well as to reduce the myths and stigma surrounding the disease. Also that month, KwaZulu-Natal became the first province to provide voluntary male medical circumcision given evidence that it reduces risk of transmission of HIV from women to men by 60%. By the end of the year, 131 117 men had been circumcised by the program.

However, by the end of 2010 only 55 percent of people who needed ARV treatment were receiving it, falling significantly short of the government’s goal of 80 percent coverage. Similarly, only 36 percent of South African children deemed eligible for HIV treatment had access to ARVs, leaving 196,000 HIV-positive children without the drugs they needed. The government maintained its commitment to rectifying these statistics over the next several years. There has been steady progress since, and by 31 May 2011 Health Minister Motsoaledi proudly announced that 11.9 million South Africans were being tested for HIV every year.

On 1 December 2011 a third National Strategic Plan (NSP) on HIV, STDs and TB was released for 2012-2016. The five goals of the plan are as follows: (1) Halve the number of new HIV infections; (2) Ensure that at least 80 percent of people eligible for HIV treatment are receiving it; (3) Halve the number of new TB infections and deaths from TB; (4) Ensure that the rights of people living with HIV are protected; and (5) Halve stigma related to HIV and TB. This plan has resulted in an increase in overall budget allocation for ARV treatment, to ensure that its second target of 80 percent coverage is reached by 2016. Dr. Thobile Mbengashe, head of the Health Department’s HIV and AIDS programme pointed out to a news reporter in April that significant progress that has been made in the last eight years, by stating: "It's actually quite extraordinary that in 2004 we had only 47 000 people on treatment and that number has really increased. By mid-2011, we had 1.79 million people. It's almost a city.” (All Africa 2012)

As of early April, R5 billion has been spent in 2012 on managing HIV treatment. This amount will reach a total of R8 billion by the end of the year. Ultimately, the introduction of widespread ARV treatment through the public health sector has made strides in altering perspectives of HIV/AIDS among South Africans. While a diagnosis of HIV used to be understood by many as a death sentence, it is increasingly seen as a treatable and manageable condition. The NSP for 2012-2016 will thus continue to shape this trend, in its promotion of a combination of multidimensional programmes for behavioral prevention, biomedical treatment, and social de-stigmatisation.

This article was written by Jodi McNeil and forms part of the SAHO Public History Internship

Avert (2011). ‘History of HIV & AIDS in South Africa,’ from AVERT: AVERTing HIV and AIDS. Available at www.avert.org [Accessed 2 March 2012]|Avert (2011). ‘HIV and AIDS in South Africa,’ from AVERT: AVERTing HIV and AIDS. Available at www.avert.org [Accessed 2 March 2012]|Butler, A., (2005). ‘South Africa’s HIV/AIDS Policy 1994-2004: How Can It Be Explained?,’ in African Affairs, Vol 104, No. 417, pp.591-614.|Bodibe, K., (2012). ‘South Africa: National Strategic Plan 2012-2016- Living With Aids,’ from All Africa, 12 April [online]. Available at www.allafrica.com [Accessed 15 April 2012]|Department of Health (2000). HIV/AIDS/STD Strategic Plan for South Africa 2000-2005. Available at www.info.gov.za [accessed 2 March 2012]|Department of Health (2000). HIV & AIDS and STI Strategic Plan for South Africa 2007-2011. Available at www.info.gov.za [accessed 2 March 2012]|Department of Health (2000). National Strategic Plan on HIV, STIs and TB 2012-2016. Available at www.info.gov.za [accessed 2 March 2012]|Mbali, M., (2005). “The Treatment Action Campaign and The History of Rights-Based, Patient-Driven HIV/AIDS Activism in South Africa,” in Research Report for the University of Kwazulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society No. 29, pp.2-23.|Motsoaledi, A., (2011). Speech by Minister of Health, Dr. A. Motsoaledi, on the Health Budget Policy, from National Assembly, 31 May [online], Available at www.doh.gov.za [Accessed 2 March 2012]|Shneider, H., (2002). ‘On the fault-line: the politics of AIDS policy in contemporary South Africa,’ in African Studies, Vol 61, No.1, pp.145-165.|Shneider, H., and Fassin, D., (2003). ‘The Politics of Aids in South Africa: Beyond the Controversies,’ in British Medical Journal, Vol 326, No 7387, pp.495-497.|Zungu-Dirwayi, N., Shisana, O., Udjo, E., Mosala, T., and Seager, J., (2004). An Audit of HIV/AIDS policies In Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe, Cape Town: HSRC Press, pp.1-100.