Nelson Mandela is a figure who has undergone many transformations in the eye of the South African public as well as in the global imagination. He has played the role of terrorist, freedom fighter, struggle icon, negotiator, statesman and politician on the public stage, both in South Africa and around the world. This article will explore the ways in which these roles have changed and been shaped by events occurring both throughout Mandela’s lifetime and beyond.

He was part of the group that formed the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL), a group that continuously pushed its parent organisation to more radical positions. Due to his meteoric rise in the African National Congress (ANC) ranks during the 1940s, Mandela was viewed as a major thorn in the side of the apartheid government, serving as Secretary General of the ANCYL from 1948. By the time the Defiance Campaign began, Mandela was the leader of the ANCYL, as well as the public spokesperson and leader of the campaign itself. As a consequence, Mandela was becoming the face of the ANC and the struggle against the oppressive Nationalist government. By 1952, Mandela was the President of the Transvaal ANC as well as serving as National Deputy President. However, by this stage, both President Albert Luthuli and Mandela were banned and thus had to operate clandestinely. At this time, Mandela was viewed as political opponent of apartheid government, operating under a policy of non-violent resistance. However, as the government became increasingly more oppressive, the ANC would take the momentous step to initiate violent resistance. This would have the effect of changing Mandela’s image from political opponent to freedom fighter, or in the eyes of the apartheid government - terrorist.

In the early 1960s, Mandela was increasingly on the radar of the apartheid government’s secret police. Mandela was nicknamed the ‘Black Pimpernel’ at this time, and repeatedly frustrated the efforts of the secret police to stop his underground resistance activities. This would culminate in Mandela’s military training in Ethiopia and Morocco by the Ethiopian army and the Algerian FLN respectively. Furthemore, Mandela had been recently made Commander of the newly formed MK, the ANC’s armed wing. Correspondingly, the nations which had a vested interest in propping up the Nationalist government viewed Mandela as a troublemaker at first, escalating to a terrorist in the 1960s.This was largely due to the African National Congress itself being branded a terrorist organisation by the United States and the United Kingdom, due to its ties with communism in both China and the Soviet Union (USSR). The US and UK saw the apartheid government as a bulwark against communism in the region and thus backed up the Nationalist government’s banning of opposition parties such as the ANC, Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and South African Communist Party (SACP). Mandela’s notoriety was confined to the halls of various intelligence services and among the struggle movement within South Africa, evidenced by him being on a CIA terrorist watchlist. He was only removed from this list in 2008. Mandela was not a prominent figure on a global public level at this time, however.

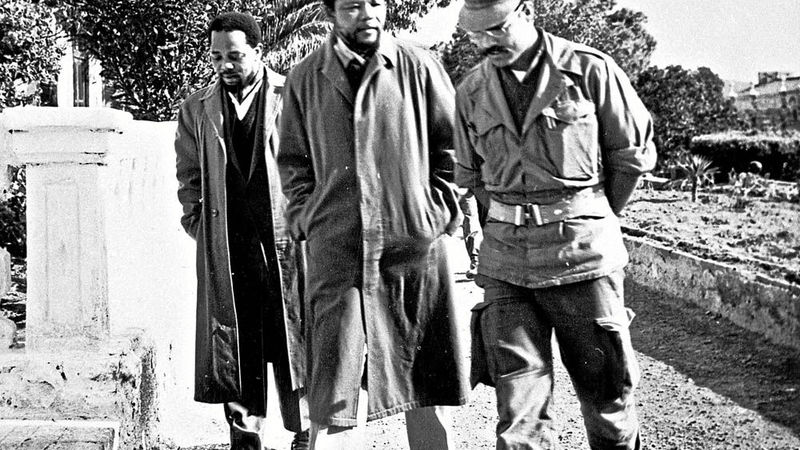

Nelson Mandela (centre) with Robert Resha (left) and Mohamed Lamari (right) Image source

Nelson Mandela (centre) with Robert Resha (left) and Mohamed Lamari (right) Image source

Following Mandela’s arrest, and the ensuing Rivonia Trial, Mandela was one of a group rather than the leader. One could argue that Mandela’s famous speech from the dock, ‘I am prepared to die’ set a process in motion that would lead to Mandela becoming one of the most famous and most idolised leaders in the world. When in prison, Mandela was once again part of a group rather than a clear leader to which people rallied around. Yet, the international perception had changed, as throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Free Mandela campaigns were run in a variety of countries, driven in a large part by the Anti-Apartheid Movement. This demonstrates that, to the public at least, Mandela had come to signify something different than his former image of ‘terrorist’. His celebrity had grown and this element of his history had been largely diluted, focusing instead on his victimhood at the hands of the apartheid government. Other prisoners at the time seemed to have realised this growth in Mandela’s celebrity with Mac Maharaj helping Mandela smuggle the first draft of his autobiography out of Robben Island prison. An editorial entitled Mandela: Man, Legend and Symbol of Resistance, Alan Cowell for the New York Times in 1985 demonstrates how Mandela was viewed while in prison, both abroad and locally: “The enigma, however, seems to be that, invisible and unheard, removed by white authority from black political activism, Mr Mandela has captured the spirit and devotion not only of those who knew him at the time of his incarceration, but also of those who have, in the last year of upheaval, assumed the custodianship of black resistance - the teenagers who were not yet born when he was jailed.” When Mandela emerged from prison in 1990, he emerged as a largely messianic figure for the South African and international public.

The South Africa which he was now a free man in, was on the brink of widespread violence. The 1980s and early 1990s had seen a significant surge in political violence in the country. The world watched with bated breath as South Africa seemed on the verge of civil war. Lwando Xaso, a lawyer who was a child during the 1980s and 1990s, writing an article entitled “Mandela the “sell out”: our memories have been blunted by time” for thejournalist.org.za, says of the violence at this time that:

“[t]he early 1990s saw a dramatic escalation in levels of violence in South Africa. I witnessed some of this violence myself. I remember seeing burning tyres around Black necks. Black mothers in unbearable pain clutching their dead children. It is reported that, from the start of the negotiations in mid-1990 to our first democratic election in April 1994, some 14 000 South Africans died in politically related violence. I have seen footage of the human carnage of Black bodies at Boipatong and Bisho. Those bodies sprawled in dust had names, hopes and dreams.”

The massacres at Boipatong and Bisho to which Xaso refers took place in June and September in 1992 respectively and claimed the lives of 72 Black South Africans. These massacres placed real pressure on the negotiations between the ANC and NP taking place at this time, resulting in the signing of the Record of Understanding between the two leaders, Mandela and F.W de Klerk, at the end of September. Xaso goes on to state in her piece that:

“Nelson Mandela must have been as weary as the rest of the country at the overwhelmingly Black rising death toll. For his quest for a lasting peaceful solution and the cessation of violence, Mandela is unfairly judged by those who will never know the weight of being the singular voice that could either incite war or peace. It can never be that today we can sit in our armchairs and judge the decisions of a man on whom so much responsibility was placed and who discharged such overwhelming responsibility to the best of his ability with who and what he knew at the time.”

Much of the criticism of Mandela as a ‘sell out’ seems to revolve around the perception that Mandela was the sole force driving negotiations. This has largely arisen due to the way in which Mandela had been made the face of the anti-apartheid struggle and, after his election as President in 1991, of the African National Congress. The negotiations between the ANC and the NP, in practice, required a number of people over many years yet Mandela was the voice of the ANC at this time, and was viewed as dictating the direction which the negotiations took.

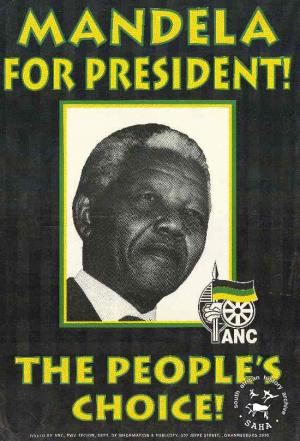

ANC poster during South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994 Image source

ANC poster during South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994 Image source

Indeed, Mandela created a public image which was the epitome of reconciliation and ‘rainbow nationism’ during the years of his presidency. Evidence of how this image had been accepted around the world can be seen in the fact that Mandela was jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 with F.W. de Klerk.The idea of the ‘rainbow nation’ was coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and represented a post-apartheid nation building project, aimed at celebrating the different cultures and people in South Africa. This project was supplemented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), brought into being by President Mandela in 1995. The commision focused on a ‘restorative justice’ rather retributive justice. Mandela’s endorsement of this process associated his own image with the concept of reconciliation. Another important part of this public image was the presentation of the 1995 Rugby World Cup trophy in South Africa. The tournament was held a year after Mandela was elected President in the first democratic elections in the country. The national rugby team, the Springboks, won the tournament fielding a largely White team. Mandela took to the field during the trophy presentation ceremony wearing a Springbok jersey, a cultural symbol of the apartheid government, in an act of reconciliation. He then presented the trophy to captain Francois Pienaar in an iconic moment in his presidency. This moment was largely viewed at the time and indeed, in hindsight, of a moment in which belief in the post apartheid South African nation building project was at an all time high. Pienaar, in his tribute at Mandela’s Cape Town memorial service in 2013, stated that “Madiba urged his comrades to keep the Springbok emblem. Fortunately, they obeyed their fearless leader’s request. We became one team playing for one country. Late in the afternoon on 24 June 1995, a nation celebrated like never before. In the true spirit of Ubuntu, for the first time ever, we were all champions together. I will never forget how proud Madiba was, and his beautiful smile.”

Following Mandela retiring from public life, he was showered with accolades from around the world (a full list of the awards and accolades can be found on the Mandela biography here).He would continue to be viewed as a great leader and was used by the ANC as a symbolic figurehead for the organisation. Mandela was present during a 2009 ANC rally alongside Jacob Zuma, then a presidential hopeful. 2009 had seen much political infighting between Zuma and then President, Thabo Mbeki over the future leadership of the ANC. The presence of Mandela at this rally is important as it demonstrates the political capital that the former president still wielded, as well as the legitimacy that Zuma gained from the association. At this time, Zuma was facing 16 counts of fraud, money laundering and racketeering. He would go on to be elected President of the ANC, and subsequently, of South Africa. Mandela was a political commodity in South Africa evidenced by the need to have him attending a variety of events such as the closing ceremony of the 2010 Soccer World Cup, hosted in South Africa. Indeed, the political opposition in South Africa have also invoked Mandela’s public persona in order to gain political legitimacy. When calling for a vote of no confidence in President Jacob Zuma in 2017, Democratic Alliance (DA) leader Mmusi Maimane invoked Mandela’s legacy by stating that, with regards to the vote, “I know what Nelson Mandela would have done”, insinuating that Mandela would have voted against Zuma.

After his death, however, there has been a rising view among young adults in South Africa that Mandela had not done enough during his presidency to help the majority Black population in South Africa. As such, Mandela’s perceived submission to big business is viewed as a betrayal at worst and a failing at best. Evidence of this can also be found in the current political sphere. DA leader Maimane, in April 2018, stated that people call him a ‘mini-Mandela’: “They say, ‘Mmusi Maimane you are a mini-Mandela! You are a sell-out of our people!’.” This demonstrates that invoking Mandela’s legacy has become a pejorative in certain groups in South Africa, particularly Black students. This arises from the failure of the economic policies, the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) from 1994 and the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) from 1996, to solve the entrenched social inequality in South Africa. The RDP set its sights on alleviating poverty and addressing the massive shortfalls in social services across South Africa.Through its RDP, the South African government aimed to fun the creation of jobs, housing and basic health care. GEAR proposed a set of medium-term policies aimed at the rapid liberalization of the South African economy. These policies included a relaxation of exchange controls, privatisation of state assets, trade liberalization, “regulated” flexibility in labour markets, strict deficit reduction targets, and monetary policies aimed at stabilizing the rand through market interest rates. Yet, despite these goals, social and economic inequality in South Africa remains among the highest in the world. Fairly or unfairly, much of the anger at this reality has been directed at these policies and President Mandela for his role in implementing them.

One can contextualise this view of Mandela by examining the #Feesmustfall protests, demonstrating a growing anger and dissatisfaction among young people, particularly Black students, at the economic inequalities in the country. Camalita Naicker, in the essay titled “From Marikana to #feesmustfall: The Praxis of Popular Politics in South Africa” states that “Within this bleak economic picture, the political crisis 20 years after democracy has been steadily deepening, with a growing number of people becoming critical of the African National Congress (ANC), together with the addition of a number of new political parties and an ever-increasing amount of NGOs and civil society organisations. [Her] paper argues that although this political crisis has, for some time now, given rise to new forms of popular politics, the new waves of students’ movements in South Africa must be seen as a part of the trajectory of popular forms of politics, particularly after the Marikana Massacre in 2012, that are rooted in political and historical memory—or older and alternative forms of politics.” This means that the mode in which the protests have taken place in recent years in South Africa can trace their roots back to such events as the 1976 student protests, yet the object of the students ire is now the ANC, as the governing party. One can argue here that, in this increasingly turbulent political and social environment, it is natural that there would be an increasing disillusion to Mandela’s cultivated public image, given the manner in which Mandela’s image has been intertwined with that of the ANC.

- https://www.fin24.com/Companies/TravelAndLeisure/Mandela-put-SA-on-the-map-SA-Tourism-20131206

- Raymond Suttner, ‘Nelson Mandela’s Leadership: The early years [Part 1]’, https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/nelson-mandelas-leadership-early-years-part-1-raymond-suttner-4-june-2018

- Antoinette Muller, ‘Francois Pienaar’s tribute: short, simply, apt’, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2013-12-12-mandela-francois-pienaars-tribute-short-simple-apt/

- News24, ‘Correction: Maimane's 'mini-Mandela' quote used out of context’, 30 April, 2018 https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/maimanes-mini-mandela-comment-sparks-social-media-uproar-20180430|

- Naledi Shange, ‘Maimane to MPs: 'I know what Mandela would have done'’, 08 August, 2017, https://www.timeslive.co.za/politics/2017-08-08-maimane-to-mps-i-know-what-mandela-would-have-done/

- Takudzwa Hillary Chiwanza, ‘Did Nelson Mandela Sell Out Black South Africans?’, 31 August, 2017, https://www.africanexponent.com/post/8556-some-people-have-suggested-that-mandela-sold-out-south-africa

- Tatenda Gwaambuka, ‘Nelson Mandela: A Saint or Sell Out?’, 1 May, 2016 https://www.africanexponent.com/post/nelson-mandela-a-saint-or-sellout-2963

- Raymond Suttner, ‘Op-Ed: Did Mandela ‘sell out’ the struggle for freedom?’, 8 March, 2016,https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2016-03-08-op-ed-did-mandela-sell-out-the-struggle-for-freedom/#.WwvpcK2adH0

- Lwando Xaso, ‘Mandela the ‘sell out’:our memories have been blunted by time’, https://www.thejournalist.org.za/spotlight/mandela-the-sell-out-our-memories-have-been-blunted-by-time

- Raymond Suttner, ‘Op-Ed: How do we understand Nelson Mandela @100’, 29 May, 2018, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-05-29-how-do-we-understand-nelson-mandela100/#.Ww1AKK2adH0

- Mihlai Ntasabo ,’ Young People on Mandela: He Could Have Done More For Us’, 21 February, 2018, https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/young-people-on-mandela-he-could-have-done-more-for-us-mihlali-ntsabo/