The Role of London in the Anti-Apartheid movement, specifically in relation to the SACP and the ANC

The international aspect of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa had many different dimensions, and many different locations. A well know resister, Ruth Slovo, was killed whilst working in Mozambique. Her work, researching Mozambique’s dependence on South Africa, would have, according to Gillian Slovo in Every Secret Thing “helped the Mozambican Government sever its economic ties with Africa, simultaneously lessening South Africa’s power to stop Mozambique from giving ANC guerrillas succor.” She was blown up with a letter bomb, the apartheid South African Government happily ignoring other states sovereign rights in its desire to maintain the status quo. This was the regime the anti-apartheid movement faced, no matter where they were.

Nor was South Africa’s intrusions into Mozambique were not isolated to this one incident. Since the beginning of the Mozambique civil war in 1977, South Africa had supported rebel groups who were attempting to destabilize the Government of Mozambique, which was at the time run by the Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO). FRELIMO was a liberation movement which was founded in 1962 to fight for the independence of the Portuguese Overseas Province of Mozambique, and was at that time run by Samora Machel. The South African Government, in its attempt to destabilize the FREMILO government, funded the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO). RENAMO was an anti-government guerrilla group under the leadership of André Matsangaissa at the time (replaced by Afonso Dhlakama after Matasangaissa was assassinated in 1979.) This support, which was causing huge damage to Mozambique and propped up the RENAMO rebels, brought the newly independent Mozambique almost to the point of collapse (an estimated 500,000 people were killed). Mozambique had only been independent since 1975. In response to this conflict, the Government of Mozambique signed the Nkomati Accord with South Africa on the 16th March, 1982. In exchange for South Africa to agree to stop funding of RENAMO, the Mozambique government promised to stop supporting the ANC, and to remove ANC members from Mozambique. This highlights the lengths that the South African government was willing to go to secure the status quo against the ANC and other anti-apartheid resistors. The struggle against the South African State was not limited to South Africa, but a conflict that involved people across the globe.

The Beginning of the international resistance and the role of Communism

The Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), although officially banned in 1950, was a large part of this international aspect. The CPSA was formed in 1921 by mainly white radical socialists and workers, but spent much of the 1920’s organizing black South Africans. From its early roots, it had strong institutional links to Great Britain. The men who set it up were predominantly British émigrés (although there were some Russians). Initially they attempted to create political institutions that resembled the ones back in Europe, and their early attempts to incorporate the issues of race were somewhat limited: “they set themselves the task of seizing power but their vision was that this would be done by the white workers with the backing of the Africans who were to be guaranteed the ‘fullest rights they are capable of exercising’.” By 1925, however, it had a majority of black workers and in 1928 called for black majority rule of South Africa.

The African National Congress (ANC) also had a long history of internationalism. In 1906, a delegation from the ANC was sent to Britain in response to the implementation of new land laws in the Orange Free State, which had stripped black residents of their legally bought land. They also sent a delegation to Britain in 1919, the petition the Government in the wake of the end of WWI. And, a delegation from the ANC attended the inaugural Congress of the League Against Imperialism, held In Brussels in 1927, where ANC members met many anti-colonial fighters from all across the world. From here, members of the ANC, including Josiah Tshangana Gumede and J. A. La Guma travelled to Germany and then the USSR.

In May of 1950, the South African government published the Suppression of Communism Act, which declared the CPSA illegal. Ruth Slovo’s husband, Joe Slovo, a prominent anti-apartheid activist and key member of the CPSA , was one of the group that illegally restarted the organization in 1953, alongside Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo and Moses Kotane. It renamed itself the South African Communist Party (SACP). Joe was a Lithuanian Immigrant who had been active in the CPSA from an early age, and was a dedicated socialist and internationalist. Ruth Slovo had travelled extensively to Prague, Moscow and then China. She visited China and Russia in 1954 as part of her work for the International union of Students and the Democratic Federation of youth. Yusuf Dadoo also had ties with the UK, having gone there to study medicine in 1929. After moving to Edinburgh at his father request, Dadoo began reading Marx and Engels, and became increasingly radicalized. The movement, therefore, had a long history of international links. In 1929, for example, Ray Alexander Simons, before immigrating to South Africa had been trained by Latvian communists in underground work. Others, such as Moses Kotane and J.B Marks had also received training in Communist International Schools. The re-created, illegal Communist Party was well versed in international affairs and struggles, and had many strong institutional links to the outside world. It would be these links that many capitalized on in their years away from South Africa.

The Introduction of Institutional Violence to the Struggle

In 1961, the banned SACP, alongside the ANC, decided to start its own militant campaign for a number of reasons (although they were somewhat influenced by a decision made by another left wing group called National Committee of Liberation to start their own campaign of sabotage.) This was done informally, amongst small discussion groups and friendship circles within the ANC as well as the SACP. The ANC initially took no formal position on the independent organization, which was to be called Umkhonto we Sizwe, or ‘Spear of the Nation’. For example, in June of 1961, the National Executive Committee debated the question of armed struggle but took no position on it. It was at this time that the SACP’s Central Committee formally agreed to endorse the establishment of this new army, although it is unclear whether this was done at a meeting or merely in agreement between the members; Ellis and Sechaba are not specific. It was the communist elements in this new organization that provided the most international assistance, and who were thus able to provide it with the support it needed. This is best highlighted by the fact that Joe Slovo and J.B Marks were sent to Moscow to organize supplies for the new army. What these specific supplies were however, and whether they managed to infiltrate them back into South Africa, is not known.

These same international contacts helped Nelson Mandela leave South Africa illegally in 1962, and travel throughout Europe and Africa. The same international connections of MK, thanks to the influence of the Communist Party members, allowed volunteers to be trained by sending them to Eastern Europe, China and other African nations. What they were trained in is not mentioned By Ellis and Sechaba, although it was most likely in propaganda or sabotage based on the training that Joe Slovo received. Despite this, in the early 1960’s the SACP and the ANC were reduced by systematic attacks from the South African Government, as typified by the 1963-1964 Rivonia trial, which saw 10 anti-apartheid activists, including Nelson Mandela, tried for 221 acts of sabotage aimed at overthrowing the South African Government. This followed the banning of liberation movements after the Sharpeville Massacre on March 22, 1960. Suring a protest South African Police shot and killed 69 protestors which led to the banning of the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) and ANC. As a result of this, many people decided to leave the country, and flee to places such as London.

London’s link to South Africa: international aspects of communism and space to rebuild

28 Penton Street N1 London: headquarters of the African National Congress 1978 to 1994

28 Penton Street N1 London: headquarters of the African National Congress 1978 to 1994

One of the main centers of this new, militant resistance was in London. It was here that the main concentration of communist party members could be found after the Rivonia trials of the mid 1960’s, as they enjoyed very close relationships with the British Communist Party (BCP). In 1960, the decolonization of Britain’s old colonial empire began in earnest, with most African colonies granted independence by 1968 (apart from the Seychelles). In England, both the Labor Party and the British Communist Party were able to put huge pressure on the Conservative Government to speed up decolonization, despite being in opposition. The UK became an important hub and space for this aspect of the resistance. Early on in the struggle, many prominent members of the resistance sought exile there, including Ruth Slovo and her family in March of 1963. She moved to Camden town in north London. The ANC was paying the rent for the house, according to Gillian Slovo, whilst Joe Slovo attempted to rebuild a smashed organization (the SACP) from 6000 miles away. Joe found his connection to the UK so useful later on in the struggle that he made sure to get hold of an illegal British passport. Meanwhile, according to her daughter, Ruth Slovo became one of the acceptable faces of South African Communism abroad, although one must recognize this is a daughter’s memory of her mother.

Another prominent member of the resistance struggle, Mac Maharaj, based himself in London, before moving back to South Africa. Like Ruth and Joe Slovo, he moved to London in exile from South Africa, and immersed himself in Communist Party circles there. Mac, like many others, was drawn to communism as a way of resisting white supremacy in South Africa. This was, according to his own testimony given to Padraig O’Malley as part of an interview, because he was not yet able to formally join the ANC, which was at the time for black Africans only, although they were closely collaborating with anyone who was against the apartheid government, regardless of skin color. The ANC became officially pan-racial on the 25 April, 1969, in the Third consultative conference in Morogoro, Tanzania. This can be seen by their relationship South African Indian Congress during the Defiance Campaign. The Defiance campaign, which occurred in 1952, was a nonviolent resistance action, which involved breaking unjust apartheid laws, such as the permit laws which banned people from moving around freely. The SACP provided another avenue of resistance that was not organized along racial lines. Mac, according to his own words, arrived in London in 1957, with the aim of studying at the London School of Economics. He was formally inducted into the South African Communist Party whilst in London, after being introduced to Vella and Patsy Pillay.

Vella Pillay had moved from South Africa to London in January 1949. During his time at university in South Africa, he became involved with other students with Marxist leanings. Through his involvement with the Transvaal Indian Congress, he was introduced to the SACP. It was through this association that he met with many of the leaders of the anti-apartheid resistance, including Nelson Mandela. With the completion of his Bachelor’s degree, he was accepted to the London School of Economics (LSE) for graduate studies. Whilst studying at the LSE, he became more involved with the BCP. His primary task became overseeing and assisting young South Africans who went to get revolutionary training in Russia and China. After the Sharpeville massacre, Vella convinced John Gollan, the secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain to send the British lawyer Ralph Milner to South Africa to contact the underground SACP resistance movement.

Mac’s flat became a gathering place for South African students who were studying in the UK. In his own words, London was a hub for revolutionaries, and full of “Nigerians, Kenyans, Tanganyikans, Burmese Indonesians, Indians, South Americans, West Indians, Irish.” The UK provided a safe place where international connections could be made and resistance activities planned away from the oppressive regimes. In fact, the UK was incredibly tolerant of some of the revolutionary activities. One of the reasons that Joe Slovo moved to the UK was that he had been declared a prohibited immigrant by the Tanzanian government, due to his communist background. Why he was declared a prohibited immigrant is not provided by the source, though it is inferred that it was due to his involvement with the SACP. London provided a safe haven for those with subversive backgrounds.

In 1960, the SACP began a journal called the African Communist, and asked those in the London unit to assist. The BCP helped its sister organization by creating a mailing address in London, and the London branch helped distribute it both in London and abroad, clandestinely. London also provided a stepping stone to further training. For example Mac Maharaj left London in March of 1961, and travelled to the German Democratic Republic, the Soviet controlled part of Germany. Here he was to be trained in sabotage and printing. Clearly London was a key part of the resistance against the South African government for many people, as it provided an initial safe space for people to recuperate and make links with other groups.

Another individual who revolved around Vella Pillay’s circle was a man called Dr Freddy Reddy. He came to London at around the same time that Mac Maharaj did, in 1957. He was radicalized in London after hearing a communist speak at Speakers Corner in Hyde Park (a side note: it is fitting that he was converted there, as this was one of the few places in Britain that during the 19th Century socialist speakers were not banned from speaking). After requesting to join the British Communist Party, he was met by Mac Maharaj, who said that whilst the British would not take him, the SACP would. He would later provide psychiatric help to some of the cadres located in the training camps in Zambian jungle. This once again highlights one of the main benefits of the London connection, which was its sheer diversity and ability to bring people together who might not have had a chance to meet in the oppressive location of South Africa.

After the Rivonia trial, the communist underground in South Africa was, according to Raymond Suttner, effectively smashed. Despite this, there were immediate, if small scale attempts to recreate the organization. In the late 1960’s, the SACP recruited and established groups within South Africa, with the aim of disseminating propaganda, such as Official publications of Both the SACP and the ANC.

Ronnie Kasrils was deeply involved in this operation. Another man who operated around Vella Pillay’s circle, he was sent to London in the mid 1960’s by the ANC, although he had already been in exile. Kasrils ended up working with leaders of the SACP such as Joe Slovo, Yusuf Dadoo, Jack Hodgson, and Robert Resha. Ronnie, however, was not part of the SACP. He first met Mac Maharaj in London, in his Golders Green flat, in North London. Ronnie provided Mac with recruits who were willing to re-enter and work within South Africa. This was the very reason that Mac had initially contacted him in London; because Ronnie had trained Sue and David Rabkin, who had infiltrated and been arrested in South Africa whilst undertaking underground work. Ronnie recruited highly dedicated volunteers in London and trained them in dangerous work, which was mostly for propaganda purposes. Initially this was just smuggling in propaganda leaflets, such as a sister of one of his contacts, who was a South African on Holiday. This soon changed, with Ronnie recruiting students studying in London, including Americans and other foreigners living there. Again, London provided a safe environment for people to gain limited formal training in propaganda distribution and how to operate in the underground before being sent back to South Africa. Ronnie Kasrils would later work in Lusaka as head of Umkhonto we Sizwe’s (Spear of the Nation’s) Military Intelligence.

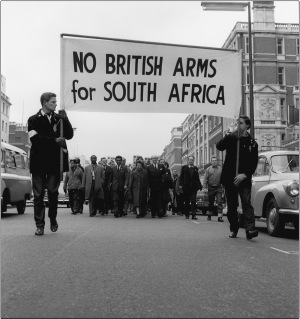

An example of propaganda produced by the Anti Apartheid Movement in the UK

An example of propaganda produced by the Anti Apartheid Movement in the UK

These volunteers, recruited in London from the British Young Communist League and other such organizations in the UK (they were not South Africans) were trained in London and then sent into south Africa, primarily to attempt to perform political propaganda actions. They used devices developed in England. These devices were street broadcasting units, which could broadcast a message into the crowded streets of the cities in South Africa. They also used leaflet bombs, which would explode and cover an area in propaganda material. These devices became increasingly complex, involving at times time delayed rockets that would blanket an large area with propaganda leaflets. These attempts had a great impact on people. The technical methods showcased that the resistance groups were well trained, which boosted peoples moral back in South Africa. Their aim was to spread propaganda messages, such as the ANC lives on and other messages to keep the ANC relevant in South Africa. These foreign activists received minimal training, and had to be taught were to plant these propaganda devices in cities they had never been in, a daunting task. These actions occurred between 1970 and 1972, in Johannesburg, Durban, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London. Through this, the resistance managed to smuggle 25 hand-picked activists into South Africa to be used for propaganda purposes, most of which was being produced outside of the country. This work was done in concert with those people recruited in South Africa, which by 1974 was established enough to be producing 25% of the material, according to Ronnie Kasrils.

London was also part of the planning the 1971-72 Chelsea Operation, commonly referred to as Aventura. This operation planned to land guerillas on the South African coast, so as to infiltrate more trained men into the country. Ronnie Kasrils, still based in London, was given the job of doing reconnaissance inside South Africa, and to organize the reception and landing points, although he did not re-enter South Africa (though he was moved to Angola in 1977). The reconnaissance group operating out of South Africa filmed and photographed the coast, trying to pick a good point of landing for these men. Despite these preparations, the entire expedition was cancelled, over fears that it was too dangerous and risky. These men were, however, eventually smuggled into South Africa over land, to begin more propaganda work and to link up with the groups in Lesotho. These devices became increasingly complex, involving at times time delayed rockets that would blanket an area with leaflets. These attempts had a great impact on people. The technical methods showcased that the resistance groups were well trained, which boosted peoples moral back in South Africa.

Yusuf Dadoo was another leader of the SACOP who was forced to flee to the UK. In the wake of the Sharpeville massacre, the SACP decided it would be best of he left the country, as he was in danger and he could give the party a greater external presence. Despite apparently disagreeing with this decision, Dadoo agreed to go abroad, and left for London. .Dadoo used the UK as a base to continue traveling abroad to garner support for the SACP, For example, in 1975 he travelled to the Congo to meet the government there.

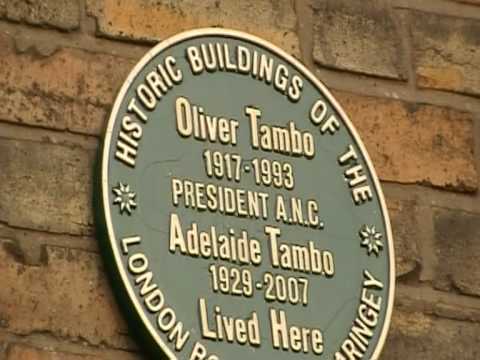

Oliver Tambo memorial plaque; Mounted on the wall of the house he lived in while he was based in London

Oliver Tambo memorial plaque; Mounted on the wall of the house he lived in while he was based in London

The ANC also sent prominent members to London. Oliver Tambo, Deputy president of the ANC, left South Africa in 1960 with the aim of setting up an external mission. Initially he moved to Ghana, but after the Ghanaian government helped him smuggle his family out they settled in London, although he was not often there. It was here that he met with Vella and Patsy Pillay, in North London. Eventually, they moved to Muswell Hill. From his base in Muswell Hill, Tambo set up and created 27 bases for the ANC worldwide. This house was funded by political donors, and it was visited in 1962 by Nelson Mandela.

The Continuing usefulness of London: Operation Vula

Joe Slovo’s continued reliance on his connection with the UK can be seen by how he ran some of the major operations out of the UK. One of these was Operation Vulindlela, a major part of which functioned specifically because of the London connection. Vulindlela, known as operation Vula, means, roughly “to open a secret way”. It was a way of dealing with the problem that had faced the ANC since 1963 which was that most of the leadership that had remained in South Africa had either been forced into exile or was imprisoned. Vula’s aim was to have high ranking ANC members smuggled into South Africa, and then set them up in South Africa in hiding, so that they could organize political and military resistance. Operation Vula represents a shift in tactics and represents a concentrated to effort for the ANC and SACP to move back in South Africa in greater numbers so that “their interventions would not happen from a distance but on the spot” Joe Slovo, of the SACP and Oliver Tambo, President of the ANC organized and led the operation. The amazing thing about Vula was that it used computer linked modems to send information. This meant that operatives inside South Africa could send reports via the London to ANC headquarters in Lusaka.

In his interview with Padraig O’Malley Tim Jenkins explains the technical wizardry as well as importance of operation Vula. Jenkins was a South African who was born in Cape Town. Because of his work for the banned SACP and the ANC, he was tried in Cape Town Supreme court, and sentenced to 12 years for distributing pamphlets. He was meant to spend 12 years in prison, from 1978 to 1990, but managed to escape in 1979.

Tim Jenkins, upon fleeing South Africa and moving to London, began to train new South African cadres in underground work. They would be sent to London to train, and then sent back into South Africa. Tim got involved with Ronnie Press, who was heading up the ANC technical committee in London. It was here that they would revolutionize communications between London and the South African operatives. Previous to this, communications had involved long, impractical code books as well as invisible ink. Ronnie and Tim turned to personal computers. Initially they received no funds from the leadership. This changed when Mac Maharaj went to London. At the time, Operation Vula was stymied with the problem of establishing proper communications channels. With Mac’s support, Tim and Ronnie made a break a breakthrough, allowing them send encrypted information from Lusaka to London. This development, which had been worked out in London, had profound effects on the resistance. Communications could now happen in a matter of days, not weeks or months. The London office compiled messages and kept records, allowing them to act as facilitators between those in South Africa and those in Lusaka. This system was extended even as far as Nelson Mandela. In 1989, Nelson Mandela, who was still in prison, was involved with communications with the Government of South Africa over the future of South Africa and the ANC. Through this system he was able to communicate with the ANC, and thus negotiate representing the ANC collective and not as in isolated leader. This was achieved by smuggling messages in with modified books. The relative safety of the space in London provided, which enabled the creation of one part of Operation Vula was one of its greatest contributions to the anti-apartheid struggle. It showed that the relative freedom in London allowed certain members of the anti-resistance movement freedom to pursue ideas that would have been unsuitable to waste time doing in a more intimate setting.

Ivan Pilay, a key member of the Operation Vula group who was based in the Lusaka base, in his interview with Padraig O’Malley, adds further explanation about the usefulness of London in the Vula operations, as well as some more details. Messages would be sent from Lusaka to London, and then from London to South Africa, as they were working under the assumption that all communications out of Lusaka were being monitored by the SA government. Further highlighting its role as a technical and training space, even the Dutch workers, who had been sent into South Africa to work there as a cover for the Vula operation were trained in London in their duties. As Tim Jenkins attests, during this time, London was a hub for Vula communications which at some points went around the world, including Amsterdam, South Africa, Lusaka and Canada.

The irony of this movement was that the more successful it was, the less use the London connection had. The whole idea of Vula was to smuggle leadership figures back into South Africa. As Operation Vula continued, more and more material could be produced internally, and was no longer produced inside of the UK. This included formal ANC and SACP publications, but also less formal propaganda, such as bumper stickers.

The Continued usefulness of London in the South African Anti-apartheid struggle

Even past the 1960’s,when the focus of the resistance as moving back to the southern African states, London still remained useful according to Mac Maharaj, the majority of the work was on, in his own words “the white side.” The London connection, however, remained useful for providing a banking connection. Tim Jenkins would work with Joe Slovo to funnel money back to SACP members working in South Africa, by smuggling in cash through a stewardess, codenamed nightingale. The money was smuggled in British Pounds, which would be exchanged on the black market. They also provided access to technical skills. Ronnie Press and Jack Hodgson, who had served in the desert rats in WWI, came up with technical ideas, such as leaflet bombs.

The London connection remained useful even when the majority of the ANC and Communist Party operations moved back to Africa and were operating out of Southern African states that had undergone decolonization, such as Mozambique and Angola. Yusuf Dodoo, Chairman of the SACP operating out of London, who has been previously mentioned, continued to receive funds from the USSR, destined for the SACP and ANC. This funding continued into the 80’s, out of the USSR embassy in the London. This showed London’s continuing importance, despite its peripheral role past the 1970’s as a source of funding for ANC and SACP activities that were then mostly located back in Africa.

London in context

Despite this, London did not remain the only foreign nation that was important to the resistance in South Africa, and must be seen in the context of a world wide effort, even if it was a limited one at that. Most of the education and formal training occurred in the Soviet Union or Soviet influenced states. For example, in 1970, Ahmed Timol, an SACP member later tasked with rebuilding the SACP in South Africa before his murder by the police in 1971, was sent to the Lenin School in Moscow. Another group was sent out in 1974 which included Keith Mokoape. Mokoape was a medical student who was involved with the South African Students Organization (SASO), and later became heavily involved in MK activities in South Africa. This group was sent instead to Egypt and the USSR, and they were successfully smuggled back into South Africa. its proximity to both the USSR and to the GDR made it an important place, even past the 1960’s.

One of the main reasons why London is important is that, like many other places such as Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, it provided a space for that allowed members to maintain the institutional memory of the ANC and the SACP, if only for a limited time before it moved back to Africa. Maintaining some of the structures of the ANC and SACP and merely the idea of struggle is important. London provided a space to do this in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre and the Rivonia trail. The underground, which was to some extent maintained by the outside and London, at least initially, helped to widen the base of support in South Africa in an incredibly harsh regime. The cadres who were trained in and sent from London, who helped create this space, were the bearers of the ANC and SACP tradition.

Close up of the ANC Headquarters Memorial Plaque

Close up of the ANC Headquarters Memorial Plaque

Work in London was not without its dangers. The apartheid government would go to great lengths to attack the ANC where ever it could, as demonstrated by the 1982 bombing of the London headquarters of the ANC. On March 14th, eight policemen from South Africa who had previously smuggled a bomb into the UK planted it into the ANC headquarters. Despite orders to avoid deaths, especially non-ANC members, the blast was large enough to demolish the entire building. Luckily, no one was killed. Other violations of state sovereignty included burglaries of ANC, Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO) offices in England. The ANC offices were targeted because, in the words of Mr. McPherson, the unit Head of Covert Strategic Communication of the South African Police the ANC offices in London “operated as if they were the foreign office of the ANC and carried a lot of authority in Europe. It was very important for us to uncover the activities indulged in by these offices and upon our visits in that area, it was very clear that trained MK members and similar persons, who were actively involved in the armed struggle, regularly visited the offices, but the British government did not want to close these offices.” This was included in his testimony in the Truth and Reconciliation commission of South Africa, which was set up to help the processes of rehabilitation by bringing to light cases of human rights abuses, and in some cases grant amnesty for these actions, and shows the effectiveness of the London operation.

Despite these dangers, when compared with the South African’s government’s attacks on other groups, London remained incredibly safe, one of the reasons why it was chosen as a center of resistance. Throughout South Africa and the states bordering, the South African government ran clandestine death squads. The South African Police security branch targeted ANC and PAC members, assassinating between 24 and 65 people between 1985 and 1991.

According to figures provided in Kevin O Briens book, the number of deaths between 1981 and 1991 were distributed thus;

- 7 in Botswana

- 2 in Swaziland

- 15 in South Africa

Institutional Support in the UK

Fund raising for the anti-apartheid struggle began in the UK in 1952, following a letter in the left leaning New Statesman in 1952, written Michael Scott. Michael Scott was a reverend who was a supporter of Namibian independence. This was much supported by E. S. Sachs, another South African who had left the country, although unlike the SACP members or the ANC, he left in a self-imposed exile. A trade union member, who had been expelled from the CPSA in 1931, he had a concrete plan to help fund activities in South Africa. The fund was called “Fund for African Democracy”. It aimed to promote legal bodies, such as the non-racial trade union groups, as opposed to the illegal ANC or Communist party. This met with lukewarm reaction in London. This fund closed in 1956, having achieved little in the way of fundraising. It was also in London that the South African Freedom Association got established. This was set up to protest against the South African regime, and the violence expected by the ANC leadership against a proposed three day stay away in April 1958. This movement grew rapidly, and included embers of the British Labor party and the Movement for Colonial Freedom.

However, whilst the Fund for African Democracy failed, others were very successful during the 1950’s. The most successful was the Treason Trial Defense Fund, which was set up after the arrests of 156 members of the Congress Alliance in 1956. Unlike the Fund for African democracy, however, this fund initially started in South Africa, by a South African Labor Party leader Alex Hepple, as well as members of the Church (which is why it became known as the Bishops fund). These South Africans appealed to exiles in London, including Trevor Huddleston, who was a member of the clergy. Huddleston had been sent to South Africa in 1943. He became active against Apartheid, and continued to work against the South African Regime after he returned to England in 1956. Huddleston immediately started to lobby in Britain, writing a letter to The Times. By the end of February, 1957, the fund stood at 7000 pounds and by April it was at 12000. Both the British Labor Party and the Trades Union Council (TRC) supported this fund, which remained above the ground, supporting legal entities in South Africa, such as the South African Labor Party and the South African Trade’s Union Organization. Despite this, the trial marked a shift in South Africa for Britain’s mainstream political left, and represented a change in the role it played as it became a central issue for the Labor Party. This became increasingly obvious in the early 1960’s. The Christian Action Defense fund, which amalgamated with the Labor parties fund in 1960, became the premier fund in the UK. Between 1960 and 1962, it attracted 150,000 pounds worth of donations, cementing this role, and in 1964 it became the central coordinating fund for all international donations to aid those facing persecution or their anti-apartheid actions. SACP links with the British Communist party and other organizations lead to the establishment of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), which helped create a global network of similar movements.

Picture of an anti-apartheid protest march

Picture of an anti-apartheid protest march

However, whilst this showed that there was support for the anti-apartheid struggle in the British mainstream political scene, it never manifested itself as full blown opposition. Despite the Labour Party had promised an arms embargo, even putting it on their election manifesto, they failed to deliver. Britain continued to supply arms to South Africa long past the 1960’s, and the Labor government never extended sanctions against the country. To compound this, frequent calls by the UN to South Africa to end apartheid, or to offer amnesty for those opposed to it, where ignored by the South African government. What did happen, however, is that apartheid remained relevant within Britain in other, non-governmental forms, including the Trade Unions. For example, Thabo Mbeki was a prominent member of the Sussex University student union.

The UK was not, however, a bastion of anti-apartheid support. Whilst there was also of space and people willing to work with the ANC and SACP members, the government of the UK continued to formally aid the South African government until the late 1980’s. This was in the context of the Cold War climate that pervaded every aspect of the time. London, either directly or via Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, provided the South African regime covert support (although how it provided aid through Moutu Sese Seko is unknown). Whilst the UK was a useful space for activists, we must not ignore the institutional aspects that supported the white regime until late in the struggle.

This article was written by Max Rossiter and forms part of the SAHO Public History Internship

Association, South African Press. "Anc Bomb in London a Warning to Uk, Williamson Tells Trc " South African Deaprtment of Justice and Constitutional Development, http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1998/9809/s980911c.htm.|

"Ruth First Bomb Maker Tells Trc He Was Following Orders " South African Department of Justice and Constitutional Development http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1998/9809/s980925a.htm.|

Barell, Howard. "Ronnie Kasrils Third Interveiw " The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv03445/04lv040….|

Commision, South African Truth and Reconciliation. "Media Hearings, Session 3." Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/special/media/media03.htm.|

Commission, South African Truth & Reconciliation. "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report." edited by Department of Justice and Constitutional Development. South Africa: South African Truth & Reconciliation Commission, 1998.|

Gerhart, Thomas G. Karis and Gail M. From Protest to Challenge; a Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa 1882-1990. Vol. 5, Indiana, USA: Indiana University Press, 1997.|

Jenkin, Tim. "Tim Jenkin: Talking with Vula." Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue, http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv03445/04lv039….|

Jordan, Z Pallo. "Joe Slovo the Revolutionary." Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue,http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02424/04lv027….|

Malley, Padraig O'. "Dr. Freddy Reddy Interveiw." The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/cis/omalley/OMalleyWeb/03lv03445/0….|

"Ivan Pillay Interveiw." Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/cis/omalley/OMalleyWeb/03lv00017/0….|

"Mac Maharaj Interveiw; 21 June 2004 " The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/cis/omalley/OMalleyWeb/03lv03445/0….|

"Ronnie Kasrils Interveiw; 10 June 2003 " The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv00017/04lv003….| Marks, Shula. "Ruth First: A Tribute." Journal of Southern African Studies 10, no. 1 (1983): 123-28.|

McKinley, Dale T. The Anc and the Liberation Struggle; a Critical Political Biography London: Pluto Press, 1997.|

McSmith, Andy. "Oliver Tambo: The Exile " The Independent, 15th October 2007.|

Meli, Francis. A History of the Anc; South Africa Belongs to Us. Indianapolis , USA: Indiana University Press, 1989.|

O'Brien, Kevin A. The South African Intelligence Services; from Apartheid to Democracy. Studies in Intelligence Series. New York, USA: Routledge 2011.|

O'Malley, Padraig. Shades of Difference; Mac Maharaj and the Struggle for South Africa New York: Viking 2007.|

O’Malley, Padraig. "Tim Je Nkin Biography." Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue, http://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02424/04lv024….|

Online, South Africa History. "Suppression of Communism Act, No. 44 of 1950 Approved in Parliament." South Africa History Online, http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/suppression-communism-act-no-44….|

Online, South African History. "Founding and Development of the Cpsa, 1921-1949." South African History Online http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/history-south-african-communist-par….|

Online, South African Hitsory. "Ronald (Ronnie) Kasrils." South African Hitsory Online, http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ronald-ronnie-kasrils.|

ahad, Essop. "Yusuf Dadoo; a Proud History of Struggle." South African Communist Party, http://www.sacp.org.za/people/dadoo.html.|

Party, South African Communist. "Ahmed Timol." South African Communist Party, http://www.sacp.org.za/main.php?ID=2290.|

Skinner, Rob. The Foundations of Anti-Apartheid; Liberal Humanitarians and Transnational Activists in Britain and the United States, C. 1919-64. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan 2010.|

Slovo, Gillian. Every Secret Thing; My Family, My Country. Great Britain Little, Brown and Company 1997.|

Stephen Ellis, Tsepo Sechaba. Comrades against Apartheid; the Anc & the South African Communist Party in Exile. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press 1992.|

Suttner, Raymond. The Anc Undeground in South Africa, 1950-1976. Boulder, Colorado, USA: FirstForumPress, 2009.|

Trust, South African Democracy Education. The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Vol. 2, South Africa: Unisa Press, 2006.